I uploaded the other two first chapters this morning. They are right below this one. Enjoy!

HI! I’m putting chapter samples of my Turtle Trilogy at the back of my new book, A One-way Cruise to Africa, and thought my blog readers might enjoy them too. Some of you may have already read the book but I have a lot of new subscribers who may have missed it.

Buy Now on Amazon

Buy Now on Amazon

A Three-Turtle Summer

The first book in the Turtle Trilogy

Janelle Meraz Hooper

Chapter 1.

A Sister in Trouble

(Grace and Glory are struggling to gain their freedom from Glory’s father)

Fort Sill, Oklahoma, July, 1949…It was too hot to play cards, especially if someone were keeping score, and Vera was. “Ay, carumba! You can’t stand to go two hours without beating someone at something can you?” Grace Tyler playfully pouted. Vera ignored her little sister, and began shuffling cards as she gleefully announced, “Senoras, the game is canasta, and we’re going to play according to Hoyle.” She began to deal the cards like a Las Vegas gambler while Pauline laughed and pointed at her mother, a notorious and frequent card-cheater. Everyone was hot, but in her long-sleeved shirt and long skirt, Grace was sweltering. Sweat beaded up on her forehead and neck and she kept stretching her legs out because the backs of her knees stuck to her skirt. “Gracie, for God’s sake, go put some shorts on,” Vera said. Grace ignored her sister, pulled her shirt away from her perspiring chest and asked, “Anyone want more iced tea before Vera whips the pants off of us?” Momma and Pauline both nodded and Grace poured tea over fresh ice cubes while Vera got a tablet and pencil out of her purse.

The room was almost silent as each woman arranged her hand. Only Momma barely tapped her foot and softly sang a song from her childhood under her breath:

“The fair senorita with the rose in her hair…

worked in the cantina but she didn’t care…

played cards with the men and took all their loot…awh-ha!

went to the store and bought brand new boots…”

“Awh-Haaa!” Grace’s five-year-old daughter Glory joined in. Unconsciously, the other two women started to hum along while they looked at their hand. About the second “Awh-Haaa!” Vera abruptly stopped humming and looked at her sisters with a raised eyebrow. Something was fishy; Momma was much too happy. Barely containing their amusement, they watched as she cheerfully arranged her cards. Finally, unable to suppress her laughter any longer, Vera jumped up, snatched the cards out of her mother’s hands, and fanned them face-up across the table. “Ay, ay, ay!” She cried out, “Momma, tell me how can you have a meld and eleven cards in your hand when we’ve just gotten started?” The fun escalated as Vera rushed around the table and ran her hands all around her mother and the chair she sat on to feel for extra cards. “Stand up!” Grace and her sisters said as they pulled their mother to her feet. They shook her blue calico dress and screamed with laughter as extra cards fell from every fold. “Glory,” Vera told her young niece, “crawl under the table and get those cards for your Auntie Vera, okay?” Grace moved her feet to the side so that her daughter could scramble under the table. Her childish giggles danced around the women’s feet as she scrambled for the extra cards that dropped from her grandmother’s dress. “Momma,” Vera laughed, “you’re a born cheater. How did you know we were going to play cards today?” she asked.

“I’m not the only one in this family who’s been caught with a few too many cards,” Momma said in her defense.

“Yes, but you’re the family matriarch. We expect better of you than we do our good-for-nothing brothers,” Pauline said.

“Huh! Matriarch, my foot. You girls never listen to a word I say,” Momma grumbled.

“Maybe that’s because we can’t trust you,” Vera said. As another card dropped from Gregoria’s dress and slid across the floor, Vera added, “We’ll strip you down to your rosary before we ever play cards with you again, Momma.”

“Yeah,” Pauline, Vera’s sister, chimed in, “the next time you’ll play in nothing but your lace step-ins and a bra made from two tortillas.”

“Well, at least I’ll be the coolest one at the table,” Momma chirped.

Vera reached across the table to gather all the cards and reshuffle them. “We’re going to start all over, and we’ll watch you every minute.”

Grace felt a sharp pain in her stomach when she looked up and saw her husband’s scowling face through the screen door. Why was he home so early? She didn’t have to look at him again to know his normally handsome blond features smoldered with disgust. Dwayne hated for Grace to have her family over. There would be trouble once her family left, since the room was heavy with the smell of pinto beans and tortillas. When they visited it was bad enough. It irked Dwayne even more when her dark-skinned family stayed for meals. “Gawd almighty!” Grace had mimicked earlier in Dwayne’s high twangy voice to her sisters, “A Texan breakin’ bread with tacos! What will folks be thinkin’?” The minute Grace’s family saw Dwayne, their laughter died, and they quickly packed up their cards, crochet cotton, and magazines that had filled a hot afternoon with laughter and joy. One by one, they lined up to leave through the back door.

Grace said a quick goodbye to her mother and sisters and moved away from the narrow doorway as the women filed past Dwayne. She held her breath as Pauline and Vera passed the loathsome soldier. She never knew what her sisters might say. All she could count on was that her mother would deliberately say something sweet to him. Always gracious, she wasn’t one to pick a fight. “Poor thing, you look absolutely beat,” Gregoria Ramirez said to Dwayne as she winked at Grace. “We’re going to get out of here so you can take a nap before dinner.” Her mother’s words were mollifying, but Gregoria didn’t walk around Dwayne to rush out the door. Instead, she stood her ground and looked him straight in the eyes until she intimidated him into stepping out of her way. When Grace’s mother stepped onto the porch she leisurely adjusted the plastic tortoise shell combs that held her long, dark hair in a bun. Then she fished her clip earrings that matched her outfit out of her dress pocket and put them back on her ears. Grace gasped when she saw her mother nonchalantly slip another extra card that was also in her pocket into her purse before she stepped onto the sidewalk.

Pauline was next in line. “Dwayne, this heat’s too much for you, it’s over a hundred today, you’d better take it easy,” she cautioned. The sound of her high heels click-click-clicked on the shiny kitchen floor and made Dwayne cringe. From the beginning of her marriage to Dwayne, Grace had been caught in the ferocious sandstorm that swirled around him and her sisters whenever they were together. Raised on a cattle ranch where his father’s booze bottles almost outnumbered the cattle, Dwayne didn’t know what to think of Pauline’s high-heeled shoes and frilly clothes. He just knew he didn’t like them. For her part, Pauline never considered making any changes to accommodate the manipulative soldier her sister had married.

Dwayne clinched his jaw and refused to let himself look down at Pauline’s high heels as she passed him, but she knew that he knew that she wore them. Always playful, she did a quick step on her way to the door. The ruffles on her colorful full skirt moved to the music her heels made as she walked. Before she passed Dwayne, she adjusted her peasant style blouse with the elastic around the top to make sure her bosom wasn’t exposed. It was a subtle movement; only Grace noticed it. Pauline lingered in the doorway as she said goodbye to Grace, then glided out the door and tossed her long, wavy black hair. The movement jangled her large, golden earrings as she crossed the threshold. “Adios, Muchacho!” she called to Dwayne, as she gave him a backward wave. Grace’s eyes flew to Dwayne to see if he noticed that her middle finger stayed up longer than the others. He didn’t. He was already looking at Vera.

“You look like hell,” Vera said as she passed a sweaty and wrinkled Dwayne, “and you could use a shower. Phew!” she added as she marched out the door. Grace saw her mother give Vera a sharp look when she got to the porch, but her oldest daughter just shrugged her chubby shoulders, as if to say it was the best she could do. This cowboy had used up all his good graces with her.

Grace wasn’t surprised Dwayne had remained quiet while her family left. She imagined that he had plenty to say; he just didn’t dare say it. Not with these women, who weren’t as meek as she was. She couldn’t tell which woman he feared the most: the mother, quiet but cunning; Vera, outspoken, tough, and fearless; or Pauline, who could cut a man to ribbons with her tongue and flirt with him at the same time. As Vera reached the sidewalk at the bottom of the porch stairs, Pauline broke into a sprint ahead of her across the yard to Vera’s car and jumped into the back seat, still giggling. Pauline had given her first gringo salute when she held up her finger to Dwayne, and she was tickled with herself. Even her mother’s look of disapproval couldn’t dampen her glee. When Gregoria opened the car door on the passenger side to get into the front, Pauline buried her face between her legs in her ruffled skirt, to muffle her laughter. Vera opened the door on the driver’s side and stopped outside the car to light a Kool and let some of the hot air out of the car before she got in. She waved a final goodbye to Grace just before she slid behind the wheel and started the old blue Cadillac. Grace’s heart ached when she saw Vera’s car move out of the parking lot. To avoid raising dust in the neighborhood, Vera drove so slowly that Grace thought about grabbing Glory and making a run for the car. But if she left now, it could make Dwayne mad enough to divorce her and file custody papers for their daughter before she was ready. She could leave her marriage anytime. The trick would be leaving with Glory. She was convinced that the courts often awarded custody of mixed blood children to white fathers because their perception was that the children would be more educated and better off economically in a white environment. It was much like the theory that Indian children would be better off if they were forcefully separated from their Indian culture and raised away from home in white schools.

***

Vera headed the old Cadillac for the highway and blew her cigarette smoke out the window as Gregoria halfheartedly said, “Vera, you must show respect to the men in the family, the way we did to Poppa.”

“When he acts like Poppa did, I’ll show respect,” Vera answered. “Did you see how mad he was? He just can’t stand to see us have a good time. I’d like to see our baby sister dump that pain-in-the-ass sourpuss. He’ll never treat her right.”

“Look where they’re living, on the far edge of the post, in old converted Army barracks. It’s worse than Dogpatch out there,” Pauline joined in.

“Yeah, it breaks my heart to see Grace married to that awful slouch. Momma, how did Poppa ever allow that?” Vera asked her mother.

“Ayyy, Vera, by the time Gracie met Dwayne, Poppa was already sick. He couldn’t stop Dwayne, and you girls were off with your new husbands,” Momma groaned. “Dwayne made your Poppa so miserable. Juan worked so hard to fit in here, and Dwayne did everything he could to make him feel like he didn’t belong. He always refused to believe your father had a college degree in engineering from the University of Mexico. He treated him like he was nothing but a cotton picker. Your poppa only picked cotton when it was the Depression, and he needed to put food on the table.” Momma dabbed at her eyes. The women nodded their heads in agreement, as if they’d never heard the stories before.

“Yeah, I remember that gun he used to carry for rattlesnakes in the fields,” Pauline jumped in. “Poppa was a perfect shot. BAM! Those snakes were dead as sticks.”

“Pauline, you don’t really believe that?” Vera laughed as she looked at her sister in the rearview mirror. “Poppa couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn with that old gun. It was loaded with snake shot. He couldn’t miss because the pellets sprayed everywhere. That’s why he always told us to stand way back.”

“Really?” Pauline asked. “I thought it was so we wouldn’t get snake blood all over us.”

Just before they dropped Pauline off at her tiny garage apartment, Vera asked, “Sis, do you and Boyd want to come over and listen to my new records tonight? I’ve got all the new ones, even Nat King Cole.”

“Naw, Boyd is off somewhere, he may not even get home for dinner,” her eyes avoided Vera’s staring suspiciously at her in the rear view mirror.

“Come without him. Benny is going to show us how to samba. You can come as you are, no one else will be there. I want to learn a new dance before Rudolf takes me to the officers’ club Saturday night.”

Pauline was obviously uneasy, but with Momma in the car, Vera couldn’t dig any deeper. Besides, if her sister were having trouble with Boyd, she’d handle it. Pauline was tough. Grace was the sister Vera was worried about. Her little sister was in over her head and too stubborn to admit it. Momma’s favorite, Grace had been kept so close to home that she’d never had any experience with men when she was growing up. At the time, Dwayne must have looked good to her naïve sister. Anyone else with more savvy would have thrown him head first into a creek and never looked back.

“Maybe. Will Grace come?” Pauline pouted, as she sank further into the back seat, her mind still on Grace’s cranky husband. “I asked her and she said she’d ask Dwayne,” Vera answered. “But you know Dwayne doesn’t like us or our music, and he has never been a dancer. He doesn’t even two-step to that country music he loves to torture us with.”

***

Her mother and sisters gone, Grace braced herself for the latest tirade from Dwayne as she started dinner. She didn’t have to wait long. Dwayne stood behind Grace and ranted at her as she breaded perch with a combination of flour and cornmeal. When she moved back and forth from the countertop by the sink to the stove, he followed her so she wouldn’t miss a word. “The fish you caught look good, Dwayne,” Grace chatted as she tried to soften his anger. It was an honest compliment. Dwayne had a lot of faults, but he was one heck of a fisherman. The day before, he’d gone fishing on the way home from work and caught a whole stringer full of perch before it started to get dark. They didn’t eat them that night because Grace already had dinner on the table when he got home. Dwayne was only briefly pleased at the compliment. Soon he was back to running down Grace’s family as she peeled potatoes to fry in one of her big wrought iron skillets. “Why the hell can’t you keep your family out of here?” Dwayne yelled as he jerked his fatigue hat off his head and threw it across the room. “What if I’d brought one of the officers from the battalion home? Do you think one of them would want to see a bunch of women sittin’ around playin’ cards and gibberin’ in Spanish the minute he walked through the door?”

“I’m sorry, Dwayne, I never thought you’d be home so early.” Grace’s lower lip quivered, and her words tumbled out on top of each other like potatoes that rolled out of an overturned sack. “But we weren’t speaking Spanish, Dwayne, we weren’t!” Grace hustled around the kitchen to get Dwayne a goblet of iced tea. She desperately wanted to go to Vera’s. Not only would it be fun but it would also keep Dwayne away from her for the evening. She knew she didn’t dare ask to go until he was in a better mood. Grace held her breath as he looked around the kitchen and gave the air an arrogant sniff before he sipped his tea.

“It’s a good thing you pepper-bellies just eat beans. Otherwise, I’d be in the poor house,” he sneered as he lit a Camel. It wasn’t just the food. Dwayne even resented her mother and sisters when they brought the food with them. He never hid the fact that he felt her family wasn’t worth his time. Only Rudolf, Vera’s husband, an Army colonel, ever got more than a few grunts from him.

“I’m sorry, Dwayne. It’s just that they were here all day, and we got so hungry, and Glory had to eat something. I just warmed up some leftover beans and Momma made a few tortillas. It was nothing fancy.”

“It’s a dog-eat-dog world, Grace.” Dwayne lit another cigarette from what was left of the last one. “And we’re not rich. We’ve got to spend our time and money on the people who can do us some good.” Dwayne finished his iced tea and left the glass on the table, where a puddle of condensation formed at its base and crept like a bleeding wound across the old table with the red, marbleized plastic top. The pattern of the moisture disturbed Grace and she hurried to wipe it up.

“Okay. Vera invited us over tonight. Everybody will be there. Benny’s going to be there to show Vera how to samba, and I haven’t seen him for a while. But, if you don’t want to go, I’ll call and say we’re staying home.”

“We were invited to Vera’s? Is Rudolf going to be there?” When Grace nodded yes, she noticed his interest perked up. “Call them,” he urged, “tell them we’ll be over as soon as we eat. In this man’s Army, it could come in real handy to be on good terms with a colonel.” On his way down the hall to change out of his uniform, he said loudly over his shoulder so Grace could hear, “And I’ve got a business idea to talk over with your mother.”

Grace, who was at the stove serving the fish and fried potatoes on plates, rolled her eyes. Just what made him think her mother would be interested in one of his screwy business plans? “Call her,” Dwayne shouted again from the bathroom. Grace went to the bathroom and stood outside the door. “There’s no need to call her. She said to come if we could,” Grace explained. “I think she’s just serving drinks and that cocktail cereal-mix she makes up in the oven. It’ll be an early night since everyone has to work tomorrow.” As soon as they ate, Grace ran to get herself and Glory ready to go before something happened to change Dwayne’s mind.

***

Even though she hurried, when the Tylers pulled into Vera’s driveway, everyone else was already there. Her brother Benny was in the large living room of the old house with Vera, demonstrating his latest dance step. Vera, who’d always been a quick study, followed right along. “Gracie,” Benny called to Grace, “come dance with me. Vera’s already got it.”

“Is this the samba?” Grace asked, bubbling over with excitement. On his way to Grace, Benny grabbed Glory and twirled her around the living room before she ran to play with her cousin Carlos, Pauline’s son. Carlos was underneath Vera’s large dining room table busily building a skyscraper out of dominos and cards.

“Glory, you’ll be a great little dancer someday,” Benny called after Glory, “just stick with your Uncle Ben.” Glory turned and giggled as she joined Carlos. Grace wasn’t surprised to see that Rudolf and Vera’s two boys hadn’t stuck around. Her nephews were already in high school and seldom hung around for their mother’s impromptu dance parties. They often teased their mother and Grace by going out the door while they sang, “It must be jelly ’cause jam don’t shake like that,” lyrics they’d heard on one of their mother’s records. The whole family—even Dwayne—laughed as Benny playfully grabbed Grace and dipped her all the way to the floor before they even started to dance. Used to her brother’s antics, she followed the movement gracefully and came up following Benny step for step, with her eyes on her brother’s feet. Rudolf sat in a corner of the living room in a big easy chair, reading the paper. When the dancers stopped to change records, his twinkling eyes peeked over the paper and he called out encouragement to Vera. Rudolf was never an enthusiastic dancer, but he liked a wife who looked good on the dance floor. Vera told Grace she could always count on Rudolf to dance the night away—as long as they played nothing but waltzes. A popular dancer, Vera was never short of partners at the Officers’ Club so she was content to let Rudolf sit and visit with their friends when they went out for the night. With barely a nod to the other members of the family, Dwayne headed for Rudolf. He was too dense to notice that the colonel pulled his paper up over his face when he saw Dwayne coming his way.

Before Dwayne could sit down in an easy chair next to the colonel, he had to move a pile of fabric and carpet swatches that Vera was using in her latest redecorating project. “Jesussss-Christ,” Dwayne said as he looked for a place to lay the handful of samples. “You oughta kick Vera’s butt for spendin’ so much of your money.”

Rudolf put down his paper and gave him a stony stare. Dwayne could barely hear him with the music blaring, so Rudolf was sure no one else heard him say, “What my wife and I do with our money is our business, Dwayne.” He didn’t say anymore before he picked up his paper and began to read again. That put Dwayne’s tail between his legs and he didn’t know what to do next. How could Rudolf not be mad as hell about the money Vera spent? He wasn’t prepared for such a rebuff. He should have shut up, but Dwayne blundered on, like a cannon rolling downhill and picking up speed as its metal wheels banged over the rocks. “Well, if it were me, I wouldn’t have no use for a woman who spent my money and did nothing but play bridge all day.” Rudolf made no reply as he gave Dwayne another icy stare and went to make himself a fresh drink. He didn’t bother to offer his brother-in-law one. Dwayne didn’t even notice the slight; he was so dumbfounded that his last statement hadn’t turned Rudolf around and made him see things his way. It was all so clear to him. Couldn’t Rudolf see Vera would drain his bank account dry? Rudolf never came back, and instead disappeared without a word into his bedroom.

Left alone with his gangly legs jutting out from the low couch, Dwayne finally made an awkward move to the other side of the room to talk to Pauline. He looked down at the high heels she wore. Well, if Rudolf wouldn’t listen to him, at least he could straighten Pauline out. “Pauline,” Dwayne said as he pointed to her feet, “the only other women I’ve seen wear shoes like that were whores. You’d better stop buying those things. People will start to talk.”

“Oh, tell me, Dwayne, have you seen a lot of whores? Where?” she asked as she rolled her eyes at her mother. Dwayne was the only man who made her husband Boyd—although he was absent—look good to her. In Spanish, she said something to her mother about Vera and snakes. He was pretty sure Pauline was telling her mother that Vera had said he was a rattlesnake. Dwayne didn’t understand the rest, but he’d heard the Spanish word for snake—serpiente—often on post. Momma nodded, and pretended to talk about Glory in Spanish, but Dwayne wasn’t fooled. He knew they were putting him down again. Dwayne was beside himself, but he didn’t want to go home until he’d accomplished his main mission: to get money from Grace’s mother for his ranch. Grace was still dancing with Benny. Vera and Pauline had joined them, so Dwayne rushed to the kitchen and poured two cups of coffee. It should be easy to get the old lady to do things his way. She didn’t even know how to read English. For sure, she’d do what he told her. “Momma, I’ve been thinkin’,” Dwayne said to his mother-in-law as he handed her a cup of coffee. “Why on earth are you still living in that big ole house by yourself? You should sell that thing and move into an apartment.”

“Why, what would I do with myself in an apartment? I’d have no garden. Besides, I’m happy where I am; all of my memories of Juan are there in that house. It’s the only home we ever had that was ours.”

“Momma, you’d better think about it, you’re getting old, and one of these days you’re gonna fall in that house and there won’t be any one there to help you. Besides, you could get a ton of money for that old place. Property values are going through the roof around here.”

“Dwayne,” said Momma, puzzled by Dwayne’s forcefulness, “I don’t need money. I live simply and I have everything I want.”

“Well,” Dwayne pushed on, “you should be thinkin’ of Glory. She’s gonna have to go to college someday, ya’ know, and if you took the money from the house and invested it in my cattle ranch, you’d have a nice little nest egg for her when she needs it.” Dwayne thought it was a pretty convincing argument; everyone knew that she adored Glory.

“Oh, so you want me to sell my house and give you the money?” Dwayne saw the beginning of a smile at the corners of Gregoria’s lips. “My coffee needs more sugar. Would you get me some?” She handed her cup to Dwayne who was glad to have an excuse to escape to the kitchen. He needed to think. What should he say next? When Dwayne could think of nothing else to say, he couldn’t control the anger he felt. He had to get out of that house before he started to beat the shit out of everyone there. In fact, if the two men hadn’t been there, things could have gotten real ugly. What makes these women so damned uppity? he wondered. When he was growing up on the ranch, his mother never dressed up and wore high heels and spent all kinds of money to decorate her house like these women did. His dad would have beat the livin’ tar out of her and told her to go feed the cows. He always told Dwayne that women who didn’t do what their husbands told them were whores and should be treated like whores. Clean and simple. No ifs, ands, or buts. With no warning, Dwayne came back to the living room and shouted, “Grace! Time to go home. Get Glory and let’s get started. Gotta work tomorrow.” He walked over to the phonograph and dragged the needle off the spinning record, putting a long scratch in it.

Startled, Grace gathered up Glory and raced out the door, while Dwayne pushed them from behind. As they got to their car, they heard the music start up again, louder than before; he was sure it was Pauline who turned the music up as a final salute to him.

***

In the car, Grace listened to Dwayne’s opinions of her family all the way home. He’d worked himself into a real good lather as he went on and on about what whores her sisters were. Grace was afraid to take her eyes off the tall, blond soldier. At any moment, she thought, he might hit her.

Dwayne held off his anger until they were in their quarters. Then his anger flew out of control. While he yelled, he pulled Grace into the hallway, where she was trapped in a space just wide enough for one person to pass. First, an arm flew out from his body and he backhanded Grace across the face and sent her into a spin to the opposite wall. When she bounced off the sheetrock, he was there to catch her. He twisted her arm behind her back and jerked it up each time he spoke. “Damn little whore. You’re just like your sisters, you’re all nothing but whores.” He pulled up on her arm again so hard that Grace cried out, but he didn’t loosen his grip. “And look at your skin. It’s as black as a colored’s. What do you do, bake in the sun while I’m at work?” He pulled up on Grace’s arm a third time. “I don’t know why I even bother with you. You’re more useless than a tit on a bullet.”

Grace crumbled in the hallway. “Stop. Please stop. You’re hurting me.”

“Damn little pepper-belly,” he raged, “I’ll show you how a real man treats whores.”

“I’m not a whore, Dwayne, and you know it,” Grace cried as she shielded her face.

“Don’t you talk back to me, don’t you dare talk back to me. I hear what the men in town say about you and your sisters.” Grace had heard it all before. Felt it all before. Belittling her made Dwayne feel important. Made him feel more like a man. Made him feel like sex. When he pulled her into the bedroom, Grace’s battered mind scurried away like a prairie mouse under sagebrush. Only the faint smell of Dwayne’s Camel cigarettes and unwashed underarm odor managed to creep underneath the mental barriers she put up to survive. Grace didn’t bother to ask anymore what the men had said; she’d heard it all before. In past fights, she had asked which men said bad things about her and her sisters, but Dwayne would never give her a name. She finally figured out that there were no “other men,” just the mean and crazy ramblings of a Texan who looked for any excuse to use his fists and feel superior. Now, she didn’t even listen to the words; she only tried to protect herself as much as she could. As he pulled Grace back to the bedroom, she saw Glory run for her closet, carrying a plate of leftover perch from the table. Grace had been so anxious to go to her sister’s that she’d forgotten to put it in the refrigerator. “Glory,” she screamed, but Dwayne pulled her back when she tried to run to their daughter.

“Dwayne, let me go. Glory has the fish. Dwayne, please, she’ll choke on the bones.” Dwayne didn’t even look Glory’s way as he threw Grace on the bed and started to unbuckle his pants. It broke Grace’s heart to know that their daughter had begun to hide in her closet as soon as she started to walk; she began to take food into the closet with her as soon as she could reach the plates on the table. Tonight, Glory ate leftover bony perch while she hid on top of a pile of her father’s duffel bags in her dark closet. But other nights, Grace had found her in the middle of the night curled around a plate of fried chicken, or cold biscuits—whatever she could grab before she ran for her bunker. When Dwayne’s anger and lust finally exhausted him, he began to cool off. Just before he went to sleep, he told Grace, “I love you Grace; I’ll try to never hit you again.” He said the same thing every time. Every time, it was a lie. And, every time, she talked herself into believing him. Why did she think he’d ever change? In the middle of the night, Grace dragged her aching body into her daughter’s room, moved the sleeping Glory from the closet, and put her in her army-issue metal bed. She shivered even though the heat was over a hundred degrees as she crawled back into bed next to Dwayne. She could have slept with Glory on her bed, but it was too small for an adult to be comfortable, and Grace was already hurting. There was no place else to go except the couch in the living room, and the one time she’d slept there, Dwayne got angry all over again. It just wasn’t worth it.

Once, the morning after a bad night, Glory asked Grace if her daddy would come after her next, and cried, “What’ll I do, Mommy? What’ll I do?” Grace looked at her panicked little face and promised her that she’d protect her if her father ever did come after her, but deep inside, she didn’t know how. She couldn’t even protect herself.

***

The next morning, Dwayne was gone before Grace put on the coffee. She sat down in the morning sun that seeped through the worn window shades and began to sew. As her machine clicked over pins and fabric at a comforting, soothing pace, she began to pull herself together. Not much longer, she told herself. Not much longer. At times, she winced as her sore ribs accidentally rubbed against the edge of the table.

Grace didn’t hear well, so she was startled when an excited voice right next to her shouted, “Mom, what are you makin’ today?” With great effort, Grace turned and lifted her daughter onto her lap. Her ribs were throbbing, so she gave her a careful but affectionate hug. While they cuddled, she pulled out the clips that held Glory’s blond hair in dog-ears. Grace ran her fingers through hair that was sticky with a combination of tears and fried fish from the night before. “We have to wash your hair today. Might as well wait until you come in for your nap, okay?” She quickly pulled Glory’s hair back into a low ponytail. Without a shampoo, there wasn’t much else she could do with it.

“Okay,” Glory readily agreed because she was anxious to go outside and play. Grace marveled at this creation with light skin, green eyes, and darkening blond hair that she’d given birth to. Her skin and hair were dark. How could a child of hers look so little like her, even with Dwayne as the father? Other children from similar marriages were a lot darker, although Dwayne was exceptionally light—he almost looked like an albino. The only other explanation was the Spanish blood on her mother’s side of the family. She knew that many of them had light hair. Strangers assumed Glory was Dwayne’s from another marriage, and Grace always smiled and said she didn’t blame them. But, deep inside, she resented it. Glory was hers, even if everything about her, from her blond hair to her long legs, looked like Dwayne.

“Hon, are you hungry?” Grace gingerly rocked Glory on her lap to avoid bumping her sore ribs into Glory. “No, what are you makin’?” Glory asked as she looked at Grace’s machine on the kitchen table. “Well, I thought my girl could use some cooler play clothes. It’s starting to get hot.”

“For me? Can I see? Oh, boy, can I have pockets?”

“You want pockets?” Grace laughed at Glory’s excitement.

“Yes. Pockets and lace.”

“Where shall I put the lace?”

“On the seat, like Linda Joy has. Her mom got her these panties with ruffles all over the seat so when she bends over all you see is ruffles, ruffles, ruffles. I love ruffles.” Glory bounced off Grace’s lap and danced around the kitchen floor, as she bent over and patted her bottom with both hands.

“What else do you want?”

“Could I have a turtle?”

“A tortuga? Where did you get that idea?”

“Linda Joy has a turtle. She calls it Fluffy. She’s teaching it to talk.”

“I’ll have to think about that. Are you sure you’re not hungry?”

“No. Sew, Mommy.”

Grace smiled to herself as she put the tiny pieces of material together. Glory was so small she could make her a whole outfit from the odds and ends leftover from the sewing she did for her relatives and friends. That was how, even on a very limited budget, Grace had filled Glory’s closet with lacy dresses, colorful play clothes, and even a rabbit fur coat. The coat, made from a couple of old rabbit stoles that Vera bought at a church bazaar, looked “Damn dandy,” Vera had said.

“When will it be finished?” Glory wanted to know as she pulled herself up over the edge of the table to get a better look at her new outfit.

“Before you know it, if you eat some breakfast and go outside and play.”

“Okay.” She stood on tiptoes to see what was on the counter, “Can I have that tortilla?”

“Yes. Why don’t you put some oleo on it?”

“If I eat it all, then can I go outside?”

“Yes,” said Grace. She watched Glory sit down on the cool floor with the flour tortilla and a small glass of red Kool-Aid; their food budget didn’t allow for extras like juice. Although, somehow, when Dwayne went to the commissary, he always found enough change for his favorites: coffee, tea, and cocoa for chocolate cakes and homemade fudge. Mostly Dwayne spent every penny he could scrounge to build up his mother’s shabby cattle ranch in Texas, even if it meant they had to cut down on food items that Glory needed, like milk and eggs. When Glory started to eat her tortilla, Grace went back to sewing. As she eased the material under the presser foot she felt a wave of anger wash over her. What kind of a breakfast was that for a little girl? Shoot! She and all her brothers and sisters ate better than that during the depression, Poppa saw to it. “If Poppa could feed all of us, why can’t this good-for-nothing son-of-a-gun feed one little girl?” Grace muttered. “And how can he think he’s such a big shot when he has money to buy food for a bunch of dumb cows, but none for his only child, who doesn’t even have milk or orange juice?” She mumbled over her sewing machine. The machine answered with click-click. Click-click. Since Grace didn’t drive, she’d have to ask her sisters to get some of the sewing money she hid from Dwayne at her mother’s and pick up a few groceries for her. Dwayne only gave her extra money for food when he felt like it—usually when he had friends come over that he wanted to impress. Sometimes, in frustration, Grace would complain that Dwayne spent too much on his ranch, but she was always fearful that she would go too far and make him angry. Besides, she told herself, any day now he’d be sent on another overseas assignment. Whole units of soldiers shipped out every day from Fort Sill on post-war assignments to occupy Japan. Most would be gone two to three years. Her plan was to wait until he left, then divorce him. Once he was out of town, it would be easier to keep custody of Glory, so why risk getting beaten again? Any day. Any day now, Grace told herself as she rested her forehead on the cool metal of her old Singer sewing machine and tried to steady her breath. Daily, Grace held onto the dream of her and Glory in a little house, living happily alone, just the two of them. She would start a sewing business; Glory would play in the backyard by the flower garden. Her heart skipped a beat whenever she dared to think she might even have a car. It wouldn’t have to be new, just something to take her to the grocery store. On the way, she pictured, she’d stop by her mother’s for coffee. Someday, she promised herself. Someday. All she had to do was be smart enough to keep Glory and get out of her marriage alive.

While she held on from day to day, Dwayne strutted his six-foot, two-inch frame around the small army quarters and acted as if he held all the cards. His favorite threat was to tell her, “I’ll take Glory away from you if you ever try to leave me. All the judges are white,” he liked to say, “and they’ll do whatever I tell them to do.” From the stories about the judges that she heard in town, Grace didn’t doubt it for a minute.

_____________________________________________________________________

Buy Now on Amazon

Buy Now on Amazon

As Brown As I Want: The Indianhead Diaries

The Adventures of Little Paintbrush and Snake Money

Janelle Meraz Hooper

1. Japanese Flu (Glory’s grade school years)

Lawton, Oklahoma, Summer of 1952—note: My name is Glory. This is my new journal. I sure hope Frieda doesn’t find it.

Dad’s supposed to be married to my mom, but he came back from an army tour of Japan dragging an awful WAC lady with him. WACs are like soldiers, only they’re women. Now my stomachaches are back, like they were before he left. My Aunt Pauline calls it the Japanese Flu, but no one else in my second grade at school has it.

My mom’s had it a couple of times, but she always seems to feel better after going to see Mr. Sparks—he’s not a doctor, he’s her attorney. I heard Aunt Pauline tell Gramma, “No man has ever given me ‘the flu’…if there’s any grief to be given out, I’ll do the giving.”

I know that’s not really true. I know for a fact that when Boyd—that was her husband—left her, she cried for days. But she’s not the type to let the world know that she’s unhappy. She’s tough as one of my gramma’s soup bones. Someday, I want to be just like her.

I don’t remember much about what went on before Dad left for Japan. My cousin Carlos says that the night before he shipped out, he made me drop my pet turtle in the snow. ’Course it froze to death. Carlos told me the next thing my dad did was beat my mom so bad that his mom—my aunt—had to take her to the hospital. I don’t know why he hit her. I think I was asleep. I get a sick feeling in my belly whenever I think about it.

Mom has never explained it to me. I wish she would because I’m afraid he’s going to beat me the way he used to beat her. I’ve never done anything to make him hit me, but then, neither did mom. So every day, I keep waiting for it to happen. It makes me real nervous. Carlos says that’s called “waiting for the other shoe to drop.” That doesn’t make sense to me. Shoes are already on the floor. Why don’t people wait for the other hat to drop?

When dad first went to Japan, I cried because he was gone. I don’t know why I missed him so much. He was a real stinker. Mom says her attorney told her it’s normal for a girl to miss her dad, even if he is a real pill. The way he talks about it, I didn’t have anyone to compare Dad with, so I couldn’t know how bad he was. That made Mom feel some better. I think that even she missed him for awhile, even though he was awful mean to her. I guess that was because he started talking real nice to her in letters—that is, until he met up with Frieda. She’s the WAC.

After Dad left, I woke up in my new bed at Aunt Vera’s house. He was gone almost three years and I’d almost forgotten about him. Then, like tornado season, he was back again. I cried when he came back because I’d really gotten used to how much fun it was without him around.

Mom was the same way. She was real happy when he was gone, but when he came back and started bothering us again, everything changed. Mom got nervous and started to shake like she did before he left because dad was always banging on our door for something. First he wanted his luggage, next he wanted their joint savings book. Next, he wanted to leave Frieda and come back home. Mom couldn’t believe it! I guess she slammed the door in his face that day. I was in school, but I heard gramma talking to Aunt Lilia about it on the phone. Aunt Lilia is my gramma’s sister-in-law and they’re real close. They tell each other everything. Sometimes they talk so much they fall asleep holding the phone.

Now dad’s settled in with Frieda and he wants me to be settled in with her too. He can’t understand why I don’t move all my stuff over there and pretend Frieda is my real mother. No wonder my stomach hurts.

I told Dad that the reason I couldn’t move over there was because Carlos—that’s my cousin—and I had gone into business together, so I needed to stick close to home. I didn’t want to come right out and say that I didn’t want to move because Dad has never been very nice to me and I don’t like his new WAC girlfriend at all.

It looks like I’m going to have the Japanese flu all summer, since Carlos and I are finished with school for the year and Dad says he wants me to spend all summer over at his house with him and Frieda. They live across the tracks on Summit Avenue. Carlos thinks they’re trying to trick me into getting used to living with them a little at a time. He says that’s how grown-ups get kids to do things they don’t want to.

A little at a time.

Then, before a kid knows it, he’s stuck somewhere he never wanted to be with people he never wanted to be with. See? Tricked! Well, it won’t work with me. I’m no dumb chicken. He’s picked the wrong cowgirl to mess with, yes siree.

Carlos is eleven and just got out of the third grade and I’m nine and going into the third grade next fall. We’re both a little behind because he needed glasses and fell behind in math, and Mom and my doctor said I should start school late because Dad had made me a nervous wreck before he left. He says I have repressed feelings. Mom says that means that I’ve pushed all my feelings way down deep inside. I don’t think that’s true. I think I just feel numb all over. Why can’t they just fix that? Anyway, they both thought I needed to rest up for awhile before I took on a new challenge. I heard Mom tell Aunt Pauline that the doctor said I was a mess, but I look fine to me.

While Dad was gone to Japan, I begged Mom not to hold me back in school because I knew that the other kids would think I was a moron, but she did anyway. She told me they’d change their minds if I made good grades. Well, I got As and Bs, but they still think I’m dumber than rainwater.

And maybe I am, because when it was really cold last winter, I let Mom and Aunt Pauline talk me into wearing a pair of Aunt Vera’s long red wool socks to school, even though I’m so skinny that they were down around my ankles all day and I kept tripping over them. If that’s not ignorant, I don’t know what is. No wonder nobody at school will hardly talk to me. Now I’ll be living those red socks down the rest of my life.

At my teacher’s conference, the teacher told my mom I didn’t fit in with the other kids because I’m backward, so I’m trying to make real sure that my desk isn’t crooked, although I’m sure it was never backward. I would have noticed. I tried to tell Mom that because she was real mad, but she wouldn’t listen. “The teacher is always right.” Mom said that when I first started school. Only now, whenever she says it, she gets real mad. So, I guess it’s true. I’m dumb, backward, and my socks are too big. I see this as all Dad’s fault, except for the socks, of course. He makes me such a nervous wreck I can’t think straight, so who knows what shape I’ll be in for the third grade next fall, after I spend time with him and Frieda this summer?

***

Here on Parkview, our moms are sisters, and the four of us—me, Mom, Aunt Pauline and Carlos—are living in their older sister’s house while she’s in Japan with her husband. That’s my Aunt Vera. There’s one more sister, my Aunt Norah, and they’re all tighter than a new pair of shoes. If you pick a fight with one of them, lookout! because all of them will be on your back before you know it.

My dad just got back from Japan and Carlos’s dad is still there until his tour of duty is up, sometime near the end of summer. That’s about when Aunt Vera and Uncle Rudolf are coming back—if they come back at all. Mom says the army could send them direct to another post, if they took a notion to.

Seems like most of the men in this family are in the military and are always being sent somewhere. I’ve got a cousin who got sent to Germany. He got a new wife while he was there. Three years later, they brought him back and sent him to Alaska but all he got there was a new dog. A husky. So far, everyone else in the family has just been sent to Japan. Dad says we’re occupying it. I guess they’ve got a lot of empty space over there to fill up.

***

Seems like Mom and Dad are going to go ahead and get the divorce. That’s fine with me. I just hope they don’t make me go live with Dad and that crazy WAC lady—that stands for Women’s Army Corps. The Army is full of them, I guess. Dad found this one in Japan. She acts like she’s The Queen of Sheba, but she’s really only a Mexican from Texas, “She’s no better than your mom,” Gramma says.

This wacky WAC is really weird. She’s always taking me to Kress Store and having me pick out things “a little girl she knows” would like. Then, when we get back to Summit Avenue, she says, “Surprise! All of this is really for you!” Why doesn’t she say it’s for me while we’re at the store? I could save her some money.

Then, after I get all this stuff that I never wanted in the first place, I’m supposed to be real grateful and give her lots of hugs and kisses, or else. I tell you, it’s really weird. But I said that already, didn’t I?

Awards:

For: As Brown As I Want: The Indianhead Diaries (The second book in my Turtle Trilogy)

1999 1st place fiction, Surrey (Canada)

2004 Oklahoma Book Award finalist.

______________________________________________________________________

Sometimes, Naked Ladies are really just old women in Capri pants…

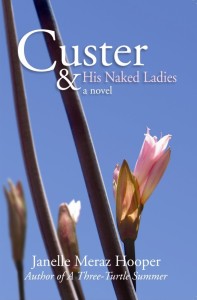

Custer & His Naked Ladies

Janelle Meraz Hooper

Buy Now on Amazon

Chapter 1. Dumped

The 3rd book in my Turtle Trilogy (Glory is a grown-up)

Glory was on her way to join her husband on a NOAA research vessel when she tried to call him to say she was running late. That was when she discovered he wasn’t on the ship; without telling her, he’d pulled out of the offshore project days before. With that failed phone call, all her recent, uncomfortable inklings fell into place. Her marriage was over. He just hadn’t gotten around to telling her yet.

That was how she ended up at Sea-Tac Airport, halfway between Seattle and Tacoma, with her hair in braids, wearing a pink Where’s the Powwow? sweatshirt. She carried only her wallet, a camera, and a faded blue gym bag. The bag was filled with the same kinds of clothes she was wearing, a few books, and a photo of her husband. The photo—frame and all—she chucked into a trash barrel outside the airport. She would have liked to toss it out of the airplane, but she was pretty sure it would make the stewards cranky if she opened the emergency exit at 35,000 feet.

Her original destination, the research vessel, was scheduled to drop anchor over the undersea volcanoes off the coast of Washington State. The scientists on the ship were to study the marine life that thrived in the hot water that spewed out of the craters.

After the research trip, she and her husband, Rick, were to take a much-needed vacation to Mexico and reconnect. They hadn’t had any identifiable problems, but her husband had been moody and refused to talk about it. Glory had hoped he would open up after a few days rest on a hot sandy beach with a Margarita in his hand. Rick hadn’t been in favor of the vacation, but Glory had insisted. Finally, he had thrown up his hands and given up.

Before the research trip, he had convinced her to put all their things in storage because they didn’t know if they’d be back in Seattle when the project was over. There was no use, he’d said, in paying rent while they were gone.

It made sense.

Sort of.

But why hadn’t she been suspicious when he’d insisted on putting all his things into separate marked boxes? How dumb was she? The dirty rat! And what would she have done on the research ship without him for three weeks? Her specialty was in freshwater turtles; there would be no real work for her there. No paycheck. He was the specialist in coastal underwater volcanoes. He belonged there. She would have been nothing more than a guest with no way off the boat. Her cheeks burned at the embarrassment she felt. What was he thinking?

Her new destination was her mother’s in Oklahoma. Getting a last-minute ticket was expensive, and Glory was thankful for her credit cards. No one ever went to Oklahoma unless they had to, and airline tickets to the Sooner State were never a bargain. Glory handed the woman at the check-in counter her credit card and mumbled a quote from a rich friend, “All it takes is money.” The woman briefly looked up, then, expressionless, continued adding up the full-fare charges on her keyboard.

On her way to the airplane boarding area, over and over, Glory thought, this isn’t the way normal, educated people get divorced.

I’ve been dumped!

With no explanation.

No discussion.

No apology!

How could this happen to me? What did I ever do to deserve this? Another phone call to him went unanswered. Finally, too frazzled and confused to try to unravel the puzzle of her husband’s behavior, and too much in shock to react in her normal, feisty way, Glory tried to force Rick out of her mind. One step at a time, she told herself. After all, she was already a rotten flyer. There was no use in taking the chance of bringing on an anxiety attack. First, she told herself, get through the plane ride to Texas without throwing up on your seatmate.

She knew she had to call her mother before she boarded her plane. Then, when she got to the Dallas-Ft. Worth Airport, she’d call Rick again. She pulled out her cell phone and pressed the speed dial number for her mother’s. It was the hardest phone call of her life—and it was short.

“Mom? I’m at the Sea-Tac Airport. I’m coming home. No, I’m alone. Rick isn’t coming.”

“Glory! What happened? Are you okay?”

“I’m okay. Rick left me.”

“I thought you two were going on a research trip?”

“I thought we were too. I guess he changed his mind.”

Glory’s sobs alarmed her mother. Over and over, she repeated, “Glory, just come

home. We’ll work out whatever it is when you get here.”

“I’ll be there around three. I’ll call you when I get to Ft. Worth.”

Afterward, she sat huddled in the waiting area for her flight with her gym bag on top of her feet to hide her shaking legs. The rest of her she pulled as far into her sweatshirt as she could, like a turtle protecting itself from a predator. Only it was too late—the predator had already struck and was smirking at her somewhere in Seattle. She pictured him sitting on a stack of cardboard boxes filled with all his earthly belongings, guzzling champagne through a snorkel. She hadn’t considered yet that, if he were devious enough to pull the research ship stunt, he probably already had his new apartment set up. She definitely hadn’t considered exactly whom he might be setting up the apartment with. That wasn’t the kind of thought you allowed yourself when you got nauseous just looking at a picture of an airplane.

She shuddered when she entered the plane’s doorway and looked down the long, claustrophobic insides of the Boeing seven thirty-seven. As she moved down the aisle between the seats, she felt the passengers behind her suddenly zig-jag from left to right. An obnoxious eight-year-old, who wore a Bellevue Elementary tee-shirt and Walkman earphones underneath her Mariner’s baseball cap, tried her best to shove her way to the front of the line through the already weary boarders.

It was the same twerp who had annoyed passengers all over C Concourse before

their delayed airplane had arrived. There was little doubt that, as soon as this little Pea Princess wannabe entered the area, airport personnel all over Sea-Tac had regretted the Please arrive two hours early for your flight signs that hung from the walls and counters of the terminal.

I’ve been dumped! The billboard that ran across the inside of her mind kept flashing. In no mood to be jostled by the upper crust, especially by a brat with a mouthful of gum blowing big blue bubbles, Glory swung her tote to the left, and successfully blocked the stampede of the Creature From the Bellevue Swamp.

“Let me by! I’m supposed to be in front,” whined the little brat, as she held her Mariner hat on her head with one hand and tried to quarterback her way past Glory.

“You are?” Glory asked incredulously, “Let me see your ticket.”

“I don’t have it,” the brat whined some more as she looked down to the front of the plane where her mother was, “but I know I’m supposed to be in 42A.”

“Sorry. No ticket, no seat. You’d better step aside and wait for your mom.”

What followed next was an earsplitting, “Mom! I need my ticket!”

Glory looked toward the back of the plane and saw her mother, a thin and fortyish-woman with a beach-in-the-box tan. She wore white cotton shorts, a tight red tank top, and white leather Keds. Her expensive sunglasses rested comfortably above her bottle-blond hairdo, and her sweater was casually tossed around her shoulders and looped in front by its sleeves. Gold chains glittered around her taunt neck.

Bellevue Mom was flirting with a young guy in shorts and a muscle shirt stamped with the word STUD on its front. Regretfully, she tore her eyes away from the hunk and looked exasperatingly in the direction of her daughter’s voice. The passengers behind Glory bunched up and filled in every inch of space as if it were a planned maneuver. There was no way they were going to let the spoiled trout swim upstream to her mother at the expense of their kneecaps. Obviously, almost everyone who was boarding the plane had already experienced the company of Ms. High Maintenance and her Bellevue Brat.

Clueless at how annoyed her fellow passengers were with her, Pea Princess jumped up and down to try to see her mother as the crowd completely blocked her view.

Hopelessness began to shorten her bounces and she finally moved to the side of the aisle and pouted as the other passengers filed past her. Smirks were abundant. One passenger gave Glory a thumbs-up. Said another, “I owe you a drink.”

“Thanks, but just promise me you’ll make a donation in my name to Planned Parenthood,” said Glory, as she tossed her gym bag under the seat in front of her. She mumbled under her breath, “My work here is done,” as she listened to the whiney voice getting drawn further and further toward the back of the plane. As she got settled, she checked out the businessman sitting next to her in the window seat; she thought she’d get acquainted.

“I’ve got good news and bad news,” she said to the man.

The man looked at the woman in her early thirties wearing jeans, Reebocks, and a ragged sweatshirt and sneered, “And what might that be?”

“The bad news is I’m a terrible flyer. The good news is I’ve taken two Dramamine. If you’ll be patient with me until we take off, the drugs will kick in and you won’t hear another peep out of me until we land at DFW.”

The man pulled his financial magazine over his face and tried to move as far away as possible in the cramped conditions. Glory tried to bite her tongue, but couldn’t resist:

“I’ll try to miss you when I throw up.” What a jerk.

Glory heard a heavy, sarcastic sigh on the other side of the man’s magazine and she whispered, “Don’t mess with me, Cowboy, I’ll throw your little pinhead out that window you’re sitting next to.” She knew he heard her; his knuckles turned white. What a lucky break. A human seatmate might have loosened her tongue, and she didn’t need to pour out all her troubles to a complete stranger. Glory tucked her pillow behind her head, covered herself with her blanket, and tried to go to sleep as the Boeing airliner rocked and rolled at a snail’s pace on its way to the runway to get into position to take off. With her eyes tightly closed, Glory prayed for the motion sickness medicine to kick in. As the plane lifted off, she briefly wondered if she was going to Oklahoma to start a new life or merely going for a visit. The answer to her question was still in Seattle; Rick was controlling her life and she didn’t like it one bit.

At the back of the plane, she could hear the Pea Princess whining; twice the flight staff told the Bellevue twerp to take her seat and belt up. Ms. High Maintenance seemed oblivious to the problems her daughter was causing. When Glory looked back, the mom’s eyes were searching the seats. No doubt, she was trying to locate the muscle shirt and the young hunk in it. Glory couldn’t locate him either. Was he hunkered down, hiding from the woman who was old enough to be his mother? He must be, Glory thought when a second scan of the plane’s interior failed to locate him.

After take-off, the drink cart passed Glory and hit her twice, once in the elbow, and once in the leg. Glory smiled sweetly when the steward apologized, but she swiped an extra can of pop off the back of the server to get even. It was easy. The steward was distracted by the Pea Princess who tried to worm her way past the cart so that she could go to the bathroom in the first-class section. “Use the bathrooms at the back of the plane, honey,” the steward suggested through gritted teeth.

“There’s already somebody in them,” the Pea Princess whined.

“They’ll be out soon,” the woman said encouragingly, “the bathrooms are full at the front too.”

Pea wasn’t convinced, but she turned around and headed toward the back. She was complaining to her mother about the mean airplane lady when a door to one of the bathrooms opened. She raced to get in front of the other passengers waiting in line, and shot past them below their kneecaps. Before they knew it, she was on the other side of a slammed bathroom door. Glory could tell by the sound her feet made as they pounded the aisle carpet that she had taken off her shoes. When she looked back, she noticed that the Pea had taken off her socks as well. And they used to call me a wild Indian, she thought.

Sadly, Glory looked at the phone on the back of the seat in front of her but resisted an urge to try to call Rick. Even if she did get him to answer, what could she say at five thousand feet in the air surrounded by strangers? Especially the man next to her. Wouldn’t he just love to hear her beg Rick to come back to her? Besides, the motion sickness medicine was kicking in. Glory was asleep before the Pea got out of the potty.

Before she went to sleep, she tried to prepare herself for what she’d find when the Saab commuter plane she’d transfer to for the final leg of her trip landed at the Lawton Airport. Her beloved family was getting smaller and smaller, much too fast.

It had started shrinking before she had ever left Oklahoma to go to college. First, they’d lost her Uncle Rudolf, her Aunt Vera’s beloved husband. He had been a real friend to a five-year-old Glory and her mother, Grace, when the two were trying to get away from Glory’s father. Rudolf’s sudden death from a heart attack had hit all of them hard. Gregoria, Glory’s grandmother, was the next to go. Her grandmother’s sister-in-law Lilia, who was also Gregoria’s best friend, followed soon after.

Someday, Glory knew, she’d have nothing but cousins. Unfortunately, Carlos, the cousin she’d grown up with, was living in New Jersey with his wife and family. She’d call him. Maybe he and Angelica could grab the kids and come down after it cooled off in August.

Glory could feel a sense of urgency in her seatmate and was about to open her eyes and move her knees over so he could go to the bathroom when she heard him mutter, “Damn Indian. Wouldn’t you know she’d sit next to me?”

After Glory heard that, she locked her knees and the man tumbled almost headfirst into the aisle. After a few more derogatory mumbles, he stumbled toward the bathroom. Glory went back to her thoughts about her family.

Tears ran down her face when she remembered the biggest loss in her life, Powwow Pete. Even before he’d married Glory’s mom, Grace, he’d watched over Glory and tried to protect her from her father, Dwayne. He’d had his hands full because her father’s stupidity and greed threatened Glory’s survival. Between her father and his second wife, Frieda, she was lucky to have survived her childhood. Before she was a teenager, each of them had tried to hasten her death so that they could collect on the accidental-death insurance policy her father had taken out on her.

Pete, who became Glory’s stepfather, had been her first choice on her new father list after her father had left Glory and her mother to marry Frieda, her stepmother. When her mother had married Pete and made her dream of having a real father come true, she never imagined that she would someday lose him. She was in college in Washington State when the news came that he had been killed in a pickup accident. She grieved over not being there to help him when he needed her; she kept telling herself that if she’d not left Oklahoma to go to college, maybe it never would have happened. Pete and Glory were inseparable when she was growing up, and Glory often rode in Pete’s pickup as he drove around the reservation conducting the tribe’s business. No one was sure how he had ended up all alone with his pickup in a ditch on the far end of the reservation. What was he doing way out there? The family thought someone must have been chasing him, but the heavy spring rains had washed away any clues.

But who would want to kill Pete? There had been a fight over who was going to manage the tribe, but Pete was fed up with tribal politics and had announced that he was going to step down way before anyone could get mad enough to murder him. Besides, tribal chairmen were recalled all the time by the Comanches without bloodshed. No one could picture a member of the tribe killing Pete, especially not over an election, but not knowing for sure had made the family distrustful of the very people Pete loved so much. Other suspects were few. If her father hadn’t been blown up in a boating accident when Glory was eight, she would have suspected him of killing Pete. Another possible suspect, her stepmother, had been run out of town soon after her father was killed, so Glory knew it wasn’t her.

Soon, the Dramamine did its job, and Glory drifted off to sleep. However, she couldn’t ignore a finger that kept poking into her upper arm. When she opened her eyes, she found herself nose to nose with the Pea Princess.

“Can I have your blanket and pillow?” the question sounded more like a demand than a request.

“Get your own,” Glory mumbled.

“They’re all gone and I’m sleepy.”

Out of the corner of her eye Glory saw the businessman’s blanket and pillow on his seat where he’d left them when he went to the bathroom.

“Here. Take these,” Glory said as she shoved the pillow and blanket into the child’s arms. The kid took off like she had a pocketful of stolen candy. Glory was almost asleep again when she heard her returning seatmate swearing under his breath. Before he even sat down, he impatiently jabbed at the service button over and over until the steward appeared.

“I need another blanket and pillow. Someone’s taken mine.”

Glory braced herself for the steward’s reply. Underneath her blanket, she dug her nails into the palm of her hand so that she wouldn’t laugh when it came:

“I’m sorry, sir, but we’re all out of blankets and pillows.”

***

Upon their arrival at the Dallas-Ft. Worth International Airport, the terminal was a crowded mix of travelers and vendors. Glory checked out the bumper of the passenger carrier that beeped as it raced past her to see if the driver had impaled any slow-moving bodies on its front grill. Surprisingly, it was bare.

The slow Texas drawl of a young woman floated atop the hurried heads and hovered over the airport noise that bounced off all its hard surfaces. Glory’s eyes followed the sound to a shoeshine booth, where a young blond woman in her twenties sat on a high leather chair and chatted easily with the black man who was busily shining her camel-colored cowboy boots with red roses tooled on their sides. Although Glory was un-noticed, she smiled in the woman’s direction, but frowned when she looked down at her own feet. She was a mess, inside and out. Her clothes in her gym bag, including a frumpy skirt, were not any better. She didn’t have to wonder what her mother and the rest of the women would think when they met her at the plane. She knew they would think the worst, but they would welcome her with open arms. Wasn’t that why people ran home when their heart was carelessly fed to a shark and their future kicked into an ocean called never? Was that the way it was going to be? Never having another home? Never having a soulmate? Never having children?

In front of Glory, a frazzled black woman walked off a covered walkway and merged with the foot traffic a few feet ahead. Suddenly, overwhelmed by the huge interior of the airport and the crowds, the woman dropped her carry-on bags on the floor in the middle of the terminal and started screaming, “Oh, Lord, help me!”

Before Glory could reach her, several businessmen stopped dead in their tracks and raced to her side. “What’s the matter?” they all asked.

“I have to get to D terminal in ten minutes to go see my sick son and I don’t know which way to go,” she sobbed.

“D terminal?” a man asked, “I’m going close to there now, come with me. I’ll get you there on time. We’ll take the tram.”

The terminal filled in like a sinkhole filling up with sand as the two moved toward the tram stairs. The hopeless sobs of the desperate woman were replaced by the sounds of women’s heels rushing to their assigned gates, the plastic wheels on the bottoms of their suitcases made a dump-dump, dump-dump sound as they sank in and out of the mortar between each ten-inch floor tile. Their sounds didn’t do anything to lighten Glory’s mood. “Dump-dump. Dump-dump!” she answered back under her breath.

Numb all over, she felt out of place as she passed groups of old ladies going in the other direction. Carrying huge metallic tote bags, they chatted gaily as they ambled happily past Glory, no doubt headed for a place in the sun that was just as hot as where they were—only with palm trees and expensive drinks served in pineapples topped with paper umbrellas. She saw so many shiny gold purses, belts, and shoes on the women that she decided Texans must be growing metallic cows.

Even though she was hungry, none of the food booths had what she craved. The yogurt had brightly colored confetti toppings that looked like plastic, the hamburgers were laced with jalapeño, and the Greek gyros looked downright nasty. Whatever happened to plain old hamburgers and fries? She passed all of the snack bars on her way to the tram and sipped her pilfered soft drink from the plane.

Before she got on the tram that would carry her to the lower level, she tried to call Rick again. No answer. She left a message. Reluctantly, she shoved her phone into her jean’s pocket. She completely forgot to call her mother as she’d promised.

Usually, Glory was fascinated by the mix of people on the lower level of the Texas airport. There, passengers gathered to catch commuter flights that flew to little dots on the map with names left over from the Old West. Places like Tishamingo, Cheyenne, Amarillo, Durango, and of course, her hometown, Lawton. More than a few real cowboys and cowgirls hung out on this level, waiting anxiously to leave what the rest of the world called civilization, and fly back to the sanity of their ranches.

Along with the cowboys and girls in Western shirts, the familiar groups of army inductees were there. Total strangers when they got to the airport, they were already bonded into tight groups and had formed friendships that would last throughout their training.

There was also the usual mix of housewives laden down with shopping bags who’d flown to Dallas for the day. Glory guessed they’d spent the day getting their gynecological exams from a doctor recommended by a friend over a bingo game at a church social. Then, they’d treated themselves to a shopping trip to Neiman-Marcus before catching a flight home. Businessmen on their way back to the small towns they came from filled in the other chairs. Big fish in little, stagnated ponds at home, Glory guessed that they’d swallowed a lot of water in Dallas. Of course, to each other, they bragged, “Business is great. I’m having a super year!”

Scattered all over the waiting room, like roses on a back fence, were young girls wearing their brother’s or boyfriend’s ivy league sweatshirts.

“Why don’t you go off to a big college and get your own sweatshirt?” Glory asked a young girl sitting across from her.

“Oh, no. I promised to wait for my boyfriend.”

“To do what?”

That was when the conversation ended. Apparently, the girl didn’t want to tell Glory that she assumed he’d rush home and marry her as soon as he graduated.

Glory ignored her silence. “You’d better wake up, Girlie. Do you think you’re going to look good to him after he spends the next four years with college girls? The next time he comes home, you’d better go back with him and crack some books. I can tell just by looking at you that you’re spending way too much time polishing your nails and dying your roots. Your brain is going to turn to bubble gum.”

The youngster went away crying. “What did I say?” Glory insincerely asked the old lady sitting next to her, although she knew exactly what she’d said and she didn’t give a damn. Women in this part of the country were treated like little Scarletts until they’d grown up. Then the tables turned, and they were supposed to be perfect wives and mothers. Never complaining, always happy with whatever crumb their husbands threw at them. About the time their nests were empty, the men were tired of their children’s mothers, and they were discarded and replaced with someone younger, greedier, and more cunning. Of course, that wasn’t the way the men saw it. In big cities, these new women were called trophy wives. In Oklahoma, they were just called sluts. Quicker than a bug hits the windshield, they squandered the money the first wife had strived to save, and the more they spent, the prouder their new husband was. As Oklahoma was not a community property state, the financial settlements in divorces were sometimes less than equitable. Wives who had devoted their lives cooking and cleaning for their husbands and children suddenly found themselves doing the same thing, at minimum wage, for strangers. She knew her own divorce settlement wouldn’t be much better. Even though Washington was a community property state, she and Rick had very little money to fight over, and no property or children. When they were together, it never seemed important; but now, Glory was giving her finances thought for the first time. She knew she’d have little left after she’d paid the few bills she had. As all of her research was on a contract basis, she didn’t have a 401-K account. She didn’t even have a car to sell.

The old lady looked up from her crochet long enough to throw Glory a disapproving look, then returned to her needlework.

“Well, bite me. Times have changed, Maudie,” Glory informed the woman. Just because the last generation of women had blindly followed each other in a long Conga Line to poverty was no reason for the newer generation of women to automatically fall in at the end of the line.

Of course, she had to admit to herself, she thought she’d done everything right, and here she was—with a degree in an overcrowded field and little else. She didn’t even have a sweatshirt with the name of an Ivy League school printed on it. A passing suitcase on wheels sang again: dump-dump, dump-dump.

2013- For: Custer & His Naked Ladies– chosen to be given away as a gift to donors to the Kickstarter for Geronimo, Life on the Reservation.

Please note:

My book website is down right now, but you can find my books on Amazon and other Internet bookstores. My thanks! Janelle

If you’ve shared this post with a friend, I thank you from the bottom of my heart, Janelle